Today's modern satellites owe a great deal of their existence to this program which inspired a rapid advancement in remote Earth sensing technology. Corona would start out as camera platform but would evolve into much more by the programs end. Although it suffered many major teething problems as such endeavors often do, the program existed in a time when repeated failures were both accepted and even expected in the march towards a usable system. It is doubtful such misfires would be tolerated today.

So urgent was the need for information during the cold war that such projects as the U-2 spy plane and Corona satellite were designed, built tested and put into operation with time line that would no doubt seem impossible to a modern day engineering team; and it was all done on drafting boards with pencils and slide rules. This paper will profile Project Corona which was emblematic of a heady era in both technology and geopolitics, the likes of which we shall likely never see again.

In 1957 the United States had a space program but it was moving at a rather lethargic pace. We sat behind a massive bomber fleet armed with nuclear bombs and were enjoying a flush economy with a sunny horizon. All of our potential enemies were across two major oceans and the Defense Early Warning line or DEW line, was an impentatrable shield of radar waves that constantly searched the skies for Russian bombers. Fighter interceptor wings ringed our borders from northern Canada to Alaska. To help keep an eye on our potential enemies project Corona, started under the name "Discoverer" as part of the WS-117L satellite reconnaissance and protection program of the US Air Force, was begun in 1956. But in October of 1957 the Russians orbited Sputnik and priorities quickly shifted.

In May 1958, the Department of Defense (DoD) directed the transfer of the WS-117L program to the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA). It was funded with a lavish $108.2 million budget for that year which, when adjusted for inflation, is about $880 million today. Add to that the Air Force and ARPA adding a combined sum of $132 million for their spinoff, the Discoverer program, and the entire project had a 1959 budget of over $1.07 billion in 2015 dollars. This gives some idea as to the importance placed on the project. The Corona project was pushed forward even more rapidly following the shooting down of a U-2 spy plane over the Soviet Union in May 1960. The American intelligence community as well as the diplomatic corps were in near panic for a way to gather intelligence without another disastrous international incident like the U-2 shoot down. This intelligence was needed in order to help prevent a misunderstanding that could help trigger World War III (Federation of American Scientists, 1995).

The Camera and Film

The Corona satellites used special 70 millimeter film with a 610 mm focal length camera. The camera was manufactured by the Eastman Kodak company and the film, was initially 0.0003 inches thick, with a resolution of 170 lines per millimeter of film. This would soon turn out to be a problematic areas in the cameras development. This was three times the resolution of the film used in WW2 just 16 years earlier but the acetate-based film was breaking in the cold of space. It was later replaced with a polyester-based film stock that was more durable in earth orbit. The amount of film carried by the satellites varied over time. Initially, each satellite carried 8,000 feet of film per camera but the reduction in the thickness of the film stock eventually allowed more film to be carried. by the fifth generation Corona the amount of film carried had been doubled to 16,000 feet by a reduction in film thickness and with additional film capsules. Most film shot was black and white but on a mission in 1964 infra red film was used and color film was used on two subsequent missions. Ironically the color film proved to have lower resolution and was never used again (National Reconnaissance Office, 2010).

New cameras were manufactured by the Itek Corporation and these had lenses that were panoramic. They moved through a 70° arc perpendicular to the direction of the orbit. A panoramic lens was chosen because it was able to obtain a wider image even though the best resolution was only obtained in the center of the image. This however was overcome by making the cameras sweep back and forth across 70° of arc since the lens on the camera was constantly rotating to counteract the blurring effect of the satellite moving over the planet (CIA, 1972).

The first Corona satellites had a single camera, but a two-camera system was quickly implemented. The front camera was tilted 15° forward, and the rear camera tilted 15° aft, so that a stereoscopic image could be obtained. Eventually the satellite had a three camera system. The third camera was employed to take "index" photographs of the objects being stereographically filmed CIA, (1972). In 1967 the cameras were placed in a drum. This drum or "rotator camera" moved back and forth, eliminating the need to move the camera itself on a reciprocating mechanism. This gave a huge improvement in image quality. The drum permitted the use of up to two filters and as many as four different exposure slits, greatly improving the variability of the Corona images The first cameras could resolve images on the ground down to 40 feet in diameter but rapid improvements in the imaging system allowed the KH-3 version of the satellite to see objects 10 feet in diameter. Later missions would be able to resolve objects just 5 feet across. A single mission was completed with a 1 foot resolution but the limited field of view was determined to be detrimental to the mission. It was later determined that a 3 foot resolution was the optimum resolution for quality of image and field of view (National Reconnaissance Office, 2010).

One early problem that cropped up was the mysterious fogging of the film. The initial Eventually, a team of scientists and engineers from the project and from determined that electrostatic discharges (ironically know as "corona discharges") caused by some of the components of the cameras were exposing the film. Corrective measures were taken but the final solution was to simply load the film canisters with a full load of film and then feed the unexposed film through the camera onto the take-up reel with no exposure. The unexposed film was then processed and inspected for corona discharges. If none was found or the corona observed was within acceptable levels, the canisters were certified for use. (National Reconnaissance Office, 2010).

How the System Worked

The first satellites in the program orbited at altitudes 100 miles above the surface of the Earth but later missions orbited even lower at 75 miles. This is about as low as an orbit can get but the idea was to get pictures and closer was better. The idea was that the cameras would take photographs only when pointed at the Earth. The Itek camera company, however, proposed to stabilize the satellite along all three axes—keeping the cameras permanently pointed at the earth. Beginning with the KH-3 version of the satellite this would be done by using a horizon camera which took images of several key stars. A sensor used the satellite's side thruster rockets to align the rocket with the selected index stars, so that it was correctly aligned with the Earth and the cameras pointed in the proper direction. It worked and by 1967 two horizon cameras were used. This system was known as the Dual Improved Stellar Index Camera or DISIC. One by one the problems were being tackled but it was still not a simple task to make the entire system work.

Once the pictures were taken the film canister was jettisoned to re-enter the atmosphere. The film was retrieved from orbit via a reentry capsule which was nicknamed the film bucket, After reentry was over, the heat shield surrounding the film bucket was jettisoned around 60,000 feet and the parachutes deployed. The capsule was intended to be caught in mid-air by a passing airplane. towing an airborne claw which would then winch it aboard or it could land at sea. In the event of a water landing there was a salt plug in the base. If it was not picked up by the United States Navy within two day this plug would dissolve and the film bucket would sink to prevent being picked up by other countries. (National Reconnaissance Office, 2010).

The CIA had a two film bucket recovery capsule system by 1969 and later even had a three film bucket system. This also allowed the satellite to go into a passive shutdown mode for up to twenty-one days before restarting and taking images again. Beginning in 1963, another improvement was made called the lifeboat. The lifeboat was a battery-powered system that allowed for ejection and recovery of the capsule if the main power system failed.

Corona had obvious short comings which resulted in the SECRET classification being dropped after a reentry vehicle accidentally landed in Venezuela. Local farmers found it in 1964 (Day, 2008). As a result a reward was offered in eight languages for the return of errant Corona film buckets to the United States.

The Politics of Corona

In 1959 there were 15 launches of the air force's Discoverer program. It had been co-developed with Corona and they had problems that became the stuff of Hollywood. Shortly after the launch of Discoverer 1 in January, an East German radio station berated the US for "launching a military satellite without giving prior warning to any nation whose territory it might pass over". It was merely a test payload with no reconnaissance capability and had not even made it into orbit but the opportunity to complain about America was too much for the East Germans to resist. Ironically Moscow did not utter a peep. In fact the Soviets did not make any comments on Discoverer 1 at all but the East Germans were furious or at least they acted that way. The Soviet silence was no surprise as the Russians had a similar program called Zenit (McDonald, 1995).

Things got worse on Discoverer 2. It carried a recovery capsule for the first time and was also the first satellite to be placed into polar orbit and the main bus performed well overall but the capsule recovery system, failed. It apparently came down near Spitsbergen Island off Norway, probably sinking in the ocean. It was never found. Rumors began shortly thereafter that the Russians had recovered the capsule but there is no evidence of this. Even if they had it was just a test vehicle and there would have been little information they could have gleaned from it. But it was too much for Hollywood writers to pass up and the cold war thriller novel and movie "Ice Station Zebra" was inspired by the incident (Day, 2009).

There was an understanding among the superpowers that they would continue to develop spy satellites and the lesser powers would simply make complaints about it. Despite the odd international incident the race for spy satellite technology continued unabated.

Improving the Technology

In fact the Corona and Discoverer missions were having a great many failures. Even though the satellites were working out most of their problems the launchers were still temperamental. The next ten Thor-Agena rockets (which carried both the Corona and Discoverer satellites) failed and were destroyed. But in August of 1959 Discoverer 13 managed a successful capsule recovery for the first time. This was also the first recovery of a manmade object from space. The Russians would duplicate the effort 9 days later, but America was the first (NASA, 2015).

Discoverer 14 carried a camera package for the first time and the cameras operated properly. The capsule was recovered from the Pacific Ocean one and a half days after launch. Then Discoverer 15 managed to successfully de-orbit its capsule but it sank into the Pacific Ocean and was not recovered. Despite this, the system was finally beginning to work.

By 1960 the Corona project was operational and in 1963, the KH-4 system with dual cameras was put into service. Once again the program was made secret, the Discoverer label was dropped and all launches became classified. Because of the increased size and weight of the satellite the basic Thor-Agena vehicle was insufficient and had to be bolstered by three solid-fueled strap-on motors (National Reconnaissance Office, 2010). On February 28, 1963, the first Thrust Augmented Thor lifted from Vandenberg carrying the first KH-4 satellite. Again failure set in as the strap-on motors failed to separate after burnout. Their dead weight dragged the Thor back down and the Range Safety Officer destroyed it. The problem was fixed and even though there were occasional failures during the next few years, the reliability rate of the program finally moved into acceptable numbers. By 1966 the best sequence of Corona missions (from 1966 to 1971) took place when there were 32 consecutive successful missions, including film recoveries.

Corona orbited in very low orbits to enhance the resolution of its camera system and at perigee (the lowest point in the orbit) and as a result Corona actually endured drag from the Earth's atmosphere causing its orbit to decay rapidly. In 1963 maneuvering rockets were added to the satellite but these were different from the attitude stabilizing thrusters. The new maneuvering rockets could boost Corona back into a higher orbit. This was no small advancement for the time. Advancements were also being made in the system's ability to be prepped and launched quickly in order to react to world events. For use during unexpected crises, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) kept a Corona ready for launch in seven days. By 1965 that time frame was down to one day.

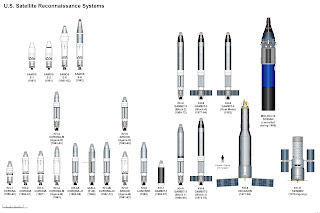

There were 6 variants of the Corona satellite of which three were variants of the KH4. They were the KH-1, KH-2, KH-3, KH-4, KH-4A and KH-4B (KH stood for "Key Hole" which was an obvious spy reference). Each model had more capabilities than the last. In all there were 218 Corona/Discoverer missions including all 30 failures (NASA, 2015). At least half of the successful missions had serious problems and only about 52 were completely successful but they all gave us vital intelligence. Eventually the Coronas would not only carry 3 film pods and enjoy an acceptably high reliability rate but they would eventually be equipped with Electronic Intelligence (ELINT) payloads also. These were known as ELINT sub satellites. Nine of the KH-4A and KH-4B missions included ELINT sub satellites, which were launched into a higher orbit. This was a harbinger of things to come.

As a backup to Corona there was an alternative program named SAMOS. This program included several types of satellite which used a different photographic methods (National Reconnaissance Office, 2015). They involved capturing images on photographic film and developing the film right there inside the satellite. The image would then be scanned and electronically transmitted via telemetry to ground stations. Essentially it was a combination Fotomat and FAX machine. The Samos satellite programs used this system but they could not take and relay very many pictures each day. Two later versions of the Samos program (the E-5 and the E-6), planned to use the Corona style film-bucket-return system and although neither of these were ever used they did show the way of the future. Eventually Corona did gave way to newer designs that could simply transmit their data. The KH-11 satellite is the modern follow on to this idea (NASA, 2015).

The End of Corona

The Corona program was so classified that is was not actually officially declassified from top secret until 1992. On February 22, 1995, the photos taken by the Corona satellites, and also by two contemporary programs (Argon and KH-6 Lanyard) were declassified by executive order. President Bill Clinton decided that enough time had passed to allow for the declassification of the Corona images. President Clinton's order also led to the declassification in 2002 of the photos from the much later model KH-7 and the KH-9 low-resolution cameras (CIA, 2015).

But from January 21st, 1959 when the first Corona test mission malfunctioned on the pad at Vandenberg AFB until the 25th of May, 1972 when the last US Air Force KH-4B photo surveillance satellite was launched from Vandenberg AFB aboard a Thor Agena D rocket, Corona was the true cutting edge eye in the sky.

References

Campbell, J. & Wynne, R., (2011). Introduction to Remote Sensing. New York, NY: The Guilford Press

CIA, (2015). Corona: Declassified. Retrieved from weblink: https://www.cia.gov/news-information/featured-story-archive/2015-featured-story-archive/corona-declassified.html

CIA, (1972), A Point in Time: The Corona Story. Retrieved from weblink: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DqYpS-A1qSA

Day, D., (2008). Spysat Down. Retrieved from weblink: http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1063/1

Day, D., (2009). Has Anybody seen our Satellite?. Retrieved from weblink: http://www.thespacereview.com/article/1352/1

Federation of American Scientists (1995). CIA Holds Landmark Symposium on CORONA. Retrieved from weblink: http://fas.org/sgp/bulletin/sec49.html

McDonald, R., (1995). Corona Between the Sun and the Earth: the first NRO reconnaissance eye in space. Bethesda, MD: The American Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing.

NASA, (2015). NSSDC Master Catalog Search. Retrieved from weblink: http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/spacecraftDisplay.do?id=1959-E01

National Reconnaissance Office, (2010). The Corona Story National Reconnaissance Office. retrieved from weblink: http://www.nro.gov/foia/docs/foia-corona-story.pdf

National Reconnaissance Office, (2015). Index, Declassified WS117L, SAMOS, and SENTRY Records. Retrieved from weblink: http://www.nro.gov/foia/declass/WS117L_Records.html

U.S. Geological Survey, (1998). Declassified Intelligence Satellite Photographs. Retrieved from weblink: https://web.archive.org/web/20070705233001/